[ENGLISH BELOW.]

A los científicos nos gustan datos y me ha gustado como los gráficos abajo del Levante-EMV muestran de manera drámatica lo seco que está aquí, ya que las DANAs de primavera y otoño no vinieron. Para entender que la crisis climática es real, solamente hay que hablar con un agricultor… Los árboles están confundidos por la precipitación alterada, ya que la única DANA del año se experimentó al inicio de septiembre, después de un verano que alcanzó aquí una máxima de más de 45 grados. Pero lo más sorprendente de todo es que ¡mi oca más grande, fuerte e inteligente (mirad la penúltima foto abajo) está poniendo! ¡En noviembre! Ya me he puesto a aprender a hornear quiche con huevos de oco (la última foto), una verdadera delicia.

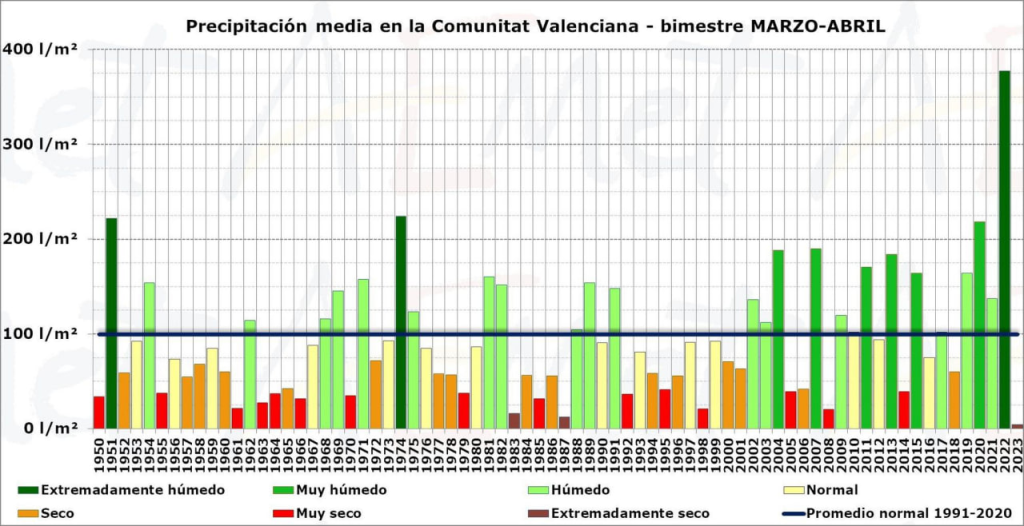

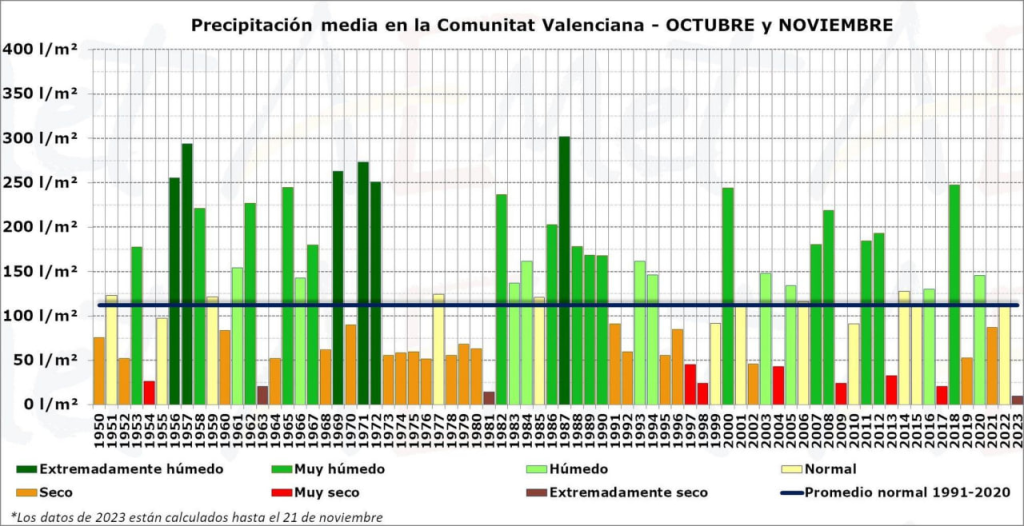

]There’s nothing like farming to highlight the effects of climate change. The Levante-EMV just published some great graphs (as a scientist, I love graphs), highlighting how the typically biannual pulses of precipitation in the Western Mediterranean have been altered. These are the March/April and Oct/Nov storms that tend to be torrential, often dropping a couple of hundred millimeters in a handful of days (but sometimes in as little as a couple of hours). Although I haven’t ever found the name in English, in Spanish it is DANA (depresión aislada en niveles altos, which I’d translate as a high-altitude isolated low pressure system). I’ve blogged about how overwhelming they were last year, in stark contrast to this year, which is the driest since record-keeping began in 1950.

With climate change, the predictions that the Atlantic storms, which tended to provide some lighter rains during the dry summer months, will no longer make it to the eastern coast of Spain (the Levante), seem to be borne out. So now we are completely dependent on these DANAs for our precipitation, and they are being altered by the elevated temperatures of the Mediterranean (a whopping 3C above normal this summer). Although last year our valley was the record holder for the entire region, with an eye-popping 170 centimeters of rain, this year we have received only 66 cm, in 3 primary pulses in February, May (thankfully in the month after the forest fire) and late Aug/Sept. It is very dry going into the citrus harvest.

It is also very warm here (it exceeded 45C this summer!!), like nearly everywhere on hothouse Earth during this El Niño year, and the trees are confused. The loquats have been in flower for a month, delighting the bees (their normal time is March), plus 3 of our 5 cherries have produced a handful of blooms and there is the occasional citrus flower to be seen (both normally happen in April).

But the most surprising of all is that Henny Penny the goose started laying eggs in mid-November! And of course she cannot be allowed to go broody at this time of year. Both the goslings would not survive but also it is a tremendous energy investment on her part during a time of year when she should be using that energy to keep herself warm. In truth, part of this is undoubtedly related to S.’s insistence on supplementing the birds’ diet (which is poor and scarce in such hot Mediterranean summers) and my research into and search for higher protein alternatives for layers. It’s working!

The photo is of Henny Penny in a nest she constructed outside the cage (it’s a long story that will have to be a separate post). It’s in a huge pile of brush next to the greenhouse, from the weeds cleared out from the previous year (note in the foreground the wild amaranth). For now I am removing all her eggs (seven so far) and replacing with duds that S. made out of their own shells and plaster. In an attempt to keep her laying, I will keep the number of duds constant at four, since I’ve observed that my geese don’t go broody with less than 5 or 6. Here is the result of goose eggs in the fall: a home-made spinach potato quiche (the crust is not mine).

For now, we farmers in my area are waiting with baited breath to see if January brings us rain, which sometimes happens. One thing is for sure, these biannual precipitation pulses can no longer be counted on. Still, most climate-change models predict a certain amount of increased precipitation for the area due to the supercharged temperatures of the Mediterranean. That is, before the inevitable desertification takes hold in the Iberian Peninsula. What better time to get a food forest established than what remains of the Roaring 20s?