La primera oquita de 2024

Disponible Otra Vez la Mandarina Regenerativa

Al lado de un mandarino medio cosechado, en la foto aparece un manzano (que a mediados de diciembre todavía no ha perdido sus hojas, ¡qué horror!). Es un ejemplo de la diversificación de cultivos que está funcionando bastante bien en Senda Silvestre. Al fondo se ve la montaña escarpada que sufrió el incendio forestal en abril. El cielo nublado tienta pero las angustiadas lluvias todavía no vienen.

Veo señales de estrés térmico e hídrico, y pienso en una nueva noticia en la revista científica Nature que nos informa que un árbol comienza a morir a los 46,7 grados. Es una temperatura a la cual no hemos llegado todavía (el record hasta ahora en nuestro valle es de 45,3 C). De los aproximadamente 80 mandarinos productivos, unos 4 o 5 se han quedado moribundos, aunque todavía con la posibilidad de recuperarse después de una buena lluvia. Este año, además, hay más fruta demasiado pequeña como para comercializar (se llevará a ‘la peladora’ para convertirse en zumo). La fruta la veo más afectada por plagas (un árbol estresado cuenta con menos energía para defenderse de ellas). Algunos campos al lado, sin embargo, han sufrido notables pérdidas de árboles enteros y el valle se ha llenado varias veces del humo de tanto quemarlos. No saco conclusiones por las diferencias que hay entre variedades, el uso de riego a manta vs. de goteo, etc.

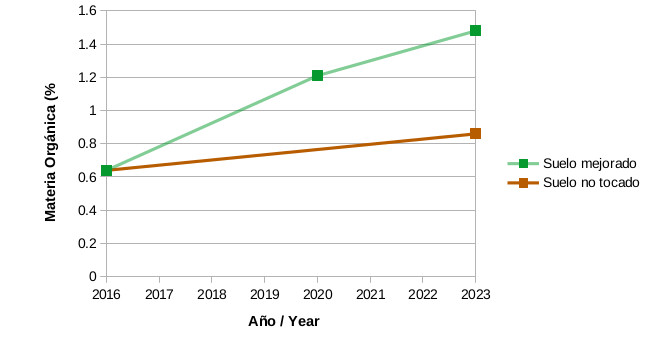

Me limito a presentar este gráfico de cuatro análisis de suelo de Senda Silvestre, para mostrar el incremento de la materia orgánica al largo del proyecto. Alcanzar un nivel de 4% sería la gran meta, pero es difícil llegar hasta allí en estas tierras semi-áridas. Pues, vamos por el bueno camino, y no nos olvidemos que esa materia orgánica proviene de gases de efecto invernadero capturados de la atmósfera. Significa menos dióxido de carbono donde no lo queremos, mientras mejora el suelo; los árboles, agradecidos, producen fruta más sabrosa.

It Never Rains But It Pours

[ENGLISH BELOW.]

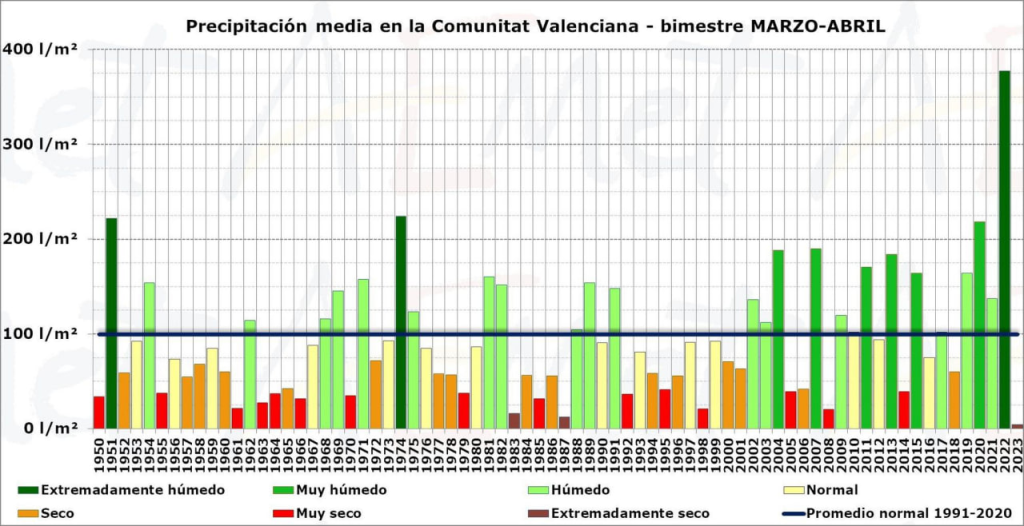

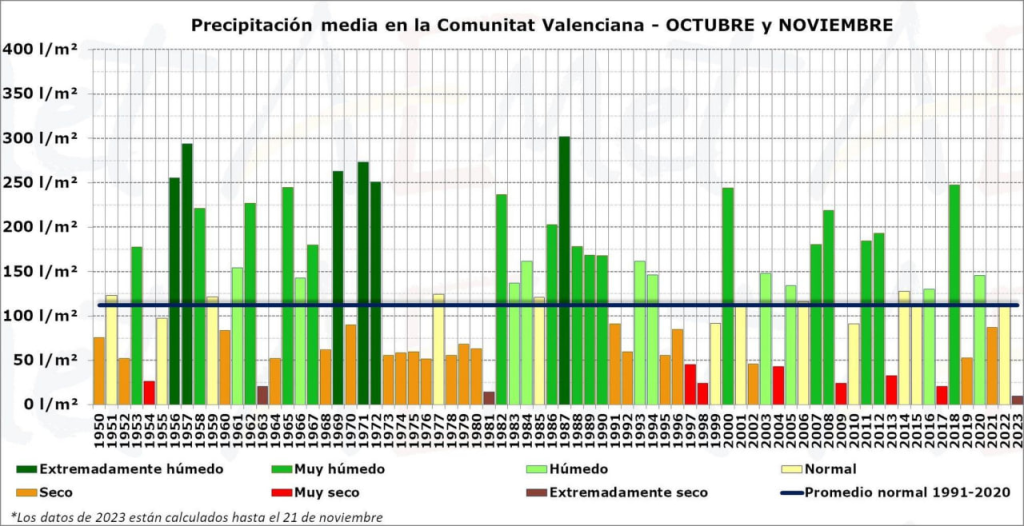

A los científicos nos gustan datos y me ha gustado como los gráficos abajo del Levante-EMV muestran de manera drámatica lo seco que está aquí, ya que las DANAs de primavera y otoño no vinieron. Para entender que la crisis climática es real, solamente hay que hablar con un agricultor… Los árboles están confundidos por la precipitación alterada, ya que la única DANA del año se experimentó al inicio de septiembre, después de un verano que alcanzó aquí una máxima de más de 45 grados. Pero lo más sorprendente de todo es que ¡mi oca más grande, fuerte e inteligente (mirad la penúltima foto abajo) está poniendo! ¡En noviembre! Ya me he puesto a aprender a hornear quiche con huevos de oco (la última foto), una verdadera delicia.

]There’s nothing like farming to highlight the effects of climate change. The Levante-EMV just published some great graphs (as a scientist, I love graphs), highlighting how the typically biannual pulses of precipitation in the Western Mediterranean have been altered. These are the March/April and Oct/Nov storms that tend to be torrential, often dropping a couple of hundred millimeters in a handful of days (but sometimes in as little as a couple of hours). Although I haven’t ever found the name in English, in Spanish it is DANA (depresión aislada en niveles altos, which I’d translate as a high-altitude isolated low pressure system). I’ve blogged about how overwhelming they were last year, in stark contrast to this year, which is the driest since record-keeping began in 1950.

With climate change, the predictions that the Atlantic storms, which tended to provide some lighter rains during the dry summer months, will no longer make it to the eastern coast of Spain (the Levante), seem to be borne out. So now we are completely dependent on these DANAs for our precipitation, and they are being altered by the elevated temperatures of the Mediterranean (a whopping 3C above normal this summer). Although last year our valley was the record holder for the entire region, with an eye-popping 170 centimeters of rain, this year we have received only 66 cm, in 3 primary pulses in February, May (thankfully in the month after the forest fire) and late Aug/Sept. It is very dry going into the citrus harvest.

It is also very warm here (it exceeded 45C this summer!!), like nearly everywhere on hothouse Earth during this El Niño year, and the trees are confused. The loquats have been in flower for a month, delighting the bees (their normal time is March), plus 3 of our 5 cherries have produced a handful of blooms and there is the occasional citrus flower to be seen (both normally happen in April).

But the most surprising of all is that Henny Penny the goose started laying eggs in mid-November! And of course she cannot be allowed to go broody at this time of year. Both the goslings would not survive but also it is a tremendous energy investment on her part during a time of year when she should be using that energy to keep herself warm. In truth, part of this is undoubtedly related to S.’s insistence on supplementing the birds’ diet (which is poor and scarce in such hot Mediterranean summers) and my research into and search for higher protein alternatives for layers. It’s working!

The photo is of Henny Penny in a nest she constructed outside the cage (it’s a long story that will have to be a separate post). It’s in a huge pile of brush next to the greenhouse, from the weeds cleared out from the previous year (note in the foreground the wild amaranth). For now I am removing all her eggs (seven so far) and replacing with duds that S. made out of their own shells and plaster. In an attempt to keep her laying, I will keep the number of duds constant at four, since I’ve observed that my geese don’t go broody with less than 5 or 6. Here is the result of goose eggs in the fall: a home-made spinach potato quiche (the crust is not mine).

For now, we farmers in my area are waiting with baited breath to see if January brings us rain, which sometimes happens. One thing is for sure, these biannual precipitation pulses can no longer be counted on. Still, most climate-change models predict a certain amount of increased precipitation for the area due to the supercharged temperatures of the Mediterranean. That is, before the inevitable desertification takes hold in the Iberian Peninsula. What better time to get a food forest established than what remains of the Roaring 20s?

Cuando marzo mayea, mayo marcea / March heatwave, May showers

[English below.]

Un antiguo refrán resume perfectamente nuestra primavera, que al inicio se ausentaba totalmente, ya que se pasó de un invierno con 2 episodios de temperaturas hasta -5C durante casi una semana, luego directamente a más de 32C en marzo. Y el colmo ha sido el incendio a mediados de abril, justamente cuando teníamos programada una práctica en Senda Silvestre para el curso de la Generalitat sobre Agricultura Regenerativa y Bosques de Alimentos. La montaña ardió durante todo un fin de semana, pero como, por suerte, no había ningún otro incendio activo en toda la región, todas las unidades convergieron en nuestro pequeño valle a salvarlo. En fin, ‘solamente’ 40 hectareas ardieron.

Llevo 4 meses queriendo acabar esta actualización, pero por un problema de la vista, no ha sido posible. Mientras tanto, han habido cambios. Hemos acogido a un gallo necesitado de rescate por ser muy agregido por el macho alfa en el campo donde nació (un poco parecido a lo que pasa con Banda Blanca, nuestra oca macho que se muestra muy agresivo con cualquier otro macho que intentamos integrar). La primera foto es de como se veía el pobre gallo al entrar. Unas semanas después, ya curado, cuando comenzó a ir detrás de las ocas (que a Banda Blanca no le gustó nada), decidimos que ya necesitaba compañía. Las gallinas (todavía jóvenes) llevan unas semanas allí, todo va bien, y ansiamos encontrar el primer huevo; calculamos que será por septiembre.

I’ve been wanting to post again for months but have been having a vision problem, so am several months behind. The forest fire burned the entire weekend and it was interesting to look at the rocky cliff that faces the farm and see the orange points of fire (some 50 the first night) being attacked by the bright white headlamps of the fire-fighters clambering over rocks I would have only thought a mountain goat could manage. We were not evacuated as there are 2 roads about 200 meters apart that separated us from the flames, which made for an interesting evening (we slept in shifts after having packed a bag of valuables, wondering if E-bikes would be fast enough to get us out if necessary).

This all came about after an extremely dry spring with temperatures in March reaching 32C (90F). The old refrain that delighted my mother (March winds and April showers/ bring forth May flowers) couldn’t be further from the truth in Spain under climate crisis. Within a week after the fire, the heat surged further to 35C (95F), which had us all sweating, literally and figuratively, but fortunately the fire didn’t spring back to life. In the fourth week of May, the spring rains finally came, albeit in an abbreviated form. In the meantime, we rescued a young rooster seriously under attack from an alpha male, and, when he started following the geese around (to which Banda Blanca did not take at all kindly), S. bought him first one and then a second companion. They are layer hens, about four months old as of July, and S. is anxiously awaiting the first egg, which should come sometime in September. The photos are of Cocky Locky in his original semi-plucked and traumatized state, and then of him as he is growing the beautiful adult plumage of his breed, Araucana or Mapuche, happy with his new consorts.

La Ironía Divina / Divine Irony

[English below.] Como si no fueran suficientemente claras las represalias del cambio climático en España, por una gran ironía, yo, de profesora en un curso para la Generalitat sobre la agricultura regenerativa como manera de afrontar el cambio climático, me encuentro con miedo por mi propia vida. Y es que un foco de fuego a apenas 300 metros de mi campo, a las 17 horas del día de hoy, se volvío un claro columna de humo tan cerca del extremo de nuestro campo, que nosotros, saliendo de casa después de la siesta, corrimos con los corazones en la boca, pensando, ¿qué demonios podría haber pasado? Llegamos y esto es lo que vimos directamente en frente:

Los bomberos nos han impresionado, y mucho, pero todavía, con todo muy claro después del puesto del sol, se aprecian unos 50 focos pequeños activos. Ni hemos llegado a la segunda mitad del mes de abril en un año en que la meteorología ya ha anunciado que será ‘abrazador’.

Sobre mañana, ni sabemos qué hacer, si seguimos con el curso, estando esta clara señal de la necesidad de efectuar tantísimos cambios, directamente a la vista.

The irony could hardly be clearer. As I was preparing to give a workshop on regenerative agriculture to combat climate change, a forest fire started about 5 PM roughly 500 meters from the farm. The wind blew it towards us, about 300 meters away at the closest point, then blew it up the rock face that faces the farm. The valley (a box canyon) is closed and there will sadly be no workshop tomorrow. It’s looking like a sleepless night…

Sisterhood / Sororidad

Tres de las cuatro ocas han acabado de poner durante esta primera nidada, que para mí ha sido demasiado pronto y muy frío para incubar; además de que a 3 les falta pareja propia. El único macho que hay, Banda Blanca, teóricamente es pareja de Goosey Lucy, aunque con este harén, hace un intento pero bastante flojo. Comenzamos a aprender cómo saber si un huevo está fecundado, empleando la prueba de trasluz. Lo que pasa es que ahora que están cluecas, se han puesto muy agresivas. Ya veremos si hay manera de coger un par de huevos y llevarlos a la oscuridad para mirar.

Las cluecas, Henny Penny y Wanda Waddler, piensan que son hermanas, y bien podría ser, aunque no lo podemos saber, porque aunque se compraron juntas de una tienda, deconocimos de cuántas madres vienen. Se han puesto a compartir un solo nido, ya que hemos cedido y les hemos dejado seis huevos, una cantidad pequeña en realidad para una oca. Y ahora, mirad ¡qué bonita sororidad! La mayoría del tiempo tornan, así disminuyendo el estrés de estar ¡TREINTA Y CINCO! días sentadas, prácticamente sin comer nada.

A la vez, como este invierno recuperamos del abandono unas 4 hanegadas de tierra, está saliendo una gran cantidad de espárragos. La tortilla de huevos de oca con espárragos está superrico. A la venta aquí.

Anunciamos una Nueva Delicia: Huevos de Oca

Ahora que nos encontramos con cuatro hembras y un solo macho, las ocas comienzan a poner. Banda Blanca, el macho único, no puede con tantas, y varios huevos salen no fertilizadas. Como cada huevo de oca equivale 3 de gallina, tantos huevos no podemos comer. A la vez, hace demasiado frío para que las ocas los incuben con éxito. Hay que esperar un tiempo mejor para evitar la experiencia del año pasado: muchísimo frío, muchísima lluvia, y apenas un solo bebé. Que por cierto, ¡ha salido hembra!

Ofrecemos 2 huevos de oca a 5 EUR. Llamad al siguiente número para pedir: seis cuatro dos nueve, doble dos, doble cero, tres.

Además, estamos trabajando un pack ‘tortilla silvestre’ que contiene 2 huevos de oca y un buen manojo de espárragos Senda Silvestre, para que preparéis la tortilla española más rica de vuestras vidas. A 10 EUR el pack. Solamente disponible en marzo. ¡Bon profit!

Introducing/ Presentación de Leo Llop

[English below.]

Ya decidido el nombre, faltaba aquí en Casa Llop un gurdián. Hace 5 años que se murío la muy querida Shakti. Este nuevo bicho, rescatado por la protectora del pueblo, bajo las típicas condiciones lamentables de todo animala abandonado, Leo lleva ya unos 5 meses aquí. Se va deshaciendo de, por supuesto, la desnutrición y flacura extrema de su tiempo en la calle, además de sus múltiples complejos (entre ellos, los coches, las bicis, la gente en general; en fin, parece que todo lo que esté en movimiento y/o que haga ruído).

Pero es una urraca; al inicio, robaba y escondía todo lo que se dejó fuera de la casa. Es aficionado particular del calzado, como todos los perros. Luego unas cosas las devolvío, comenzando con un guante mío (creo que en ese momento me conquistó). Ya, al ver que su trabajo de chatarrero le ganó mimos y cariño, se ha convertido en el recogedor de basura de las múltiples parcelas que nos rodean, la cual dispersa por las afueras de la casa. Así poco a poco va limpiado los campos abandonados a nuestro alrededor de toda seña del Antropoceno. Cada par de semanas, llena S. la carretilla con su basura junto con la de nuestras propias excavaciones aquí en casa y la lleva con la bici a unos 5 km a los contenedores más cercanos.

Hace poco pasó un señor por el Pas del Llop y, mirándole a Leo, exclamó, ‘¡Guapísimo!¡ ¿A que sí?

With a name chosen, the only thing left for Wolf House was to get a guard dog, given that it’s been over 5 years since our darling Shakti died. Rescued from the street in the typical, lamentable conditions of abandoned animals here, Leo has been with us for 5 months. Little by little he’s overcome the malnutrition and extreme underweight of his time on the street. And now we’re working on his multiple complexes (such as cars, bikes and people in general; in effect, it seems like anything that’s in motion or makes noise).

But he’s a pack rat; at first, he stole and hid anything and everything that got left outside around the house. He’s a special fan of shoes, like all dogs. After some time, he returned a glove of mine that had gone missing weeks before. And seeing the praise and pets that won him, he’s now become the trash collector for multiple plots that surround us, leaving it scattered around the house. So little by little the abandoned farms nearby are being cleared of the signs of the Anthropocene. Every couple of weeks, S. fills the bike cart with his trash together with that turned up in our own excavations at the house, and he bikes it some 5 km to the closest trash containers.

Recently a man came hiking by the house on Wolf Pass and, seeing Leo, exclaimed, ‘How gorgeous!’ Don’t you agree?